Store as HTML, Edit as LML

Back to HTML WARDen.

-

The Wiki Weekend Part 1: Motivation and Other Wikis

-

The Wiki Weekend Part 2: The Page Editor Idea

-

The Wiki Weekend Part 3: The Storage

-

The Wiki Weekend Part 4: Users, Locking

-

The Wiki Weekend Part 5: Finishing Touches, Conclusion

-

Beyond the weekend: Store as HTML, Edit as LML] (Part 7)

You are here

After the disappointing failure of my low-effort WYSIWYG editor (see Death to WYSIWYG!), I got my chance to try out the other idea I’d had.

Normally, a wiki will have its own mini-language which gets converted to HTML for viewing. For example, Wiki Creole (wikipedia.org).

Let’s use the term LML, short for Lightweight Markup Language (wikipedia.org), as the name for these wiki mini-languages.

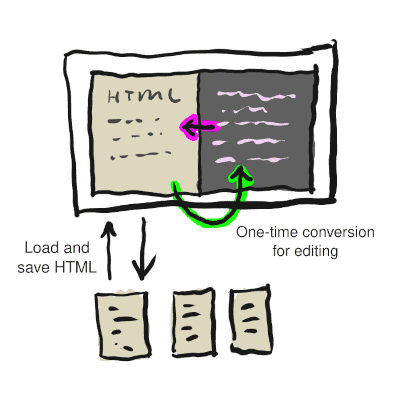

In broad strokes, this is what the process normally looks like:

-

Store pages as LML

-

Edit pages as LML

-

Render pages as HTML for viewing

The idea I’ve been brewing for a while is to do this instead:

-

Store pages as HTML

-

Edit pages as LML

No "rendering" step needed, page is already HTML!

In this model, the LML form of the page only temporarily exists as the editing format.

If you’re feeling somewhat philosophical, you could say that this method uses an LML as an interface for editing HTML.

From HTML it comes, to HTML it returns

In slightly more detail, the lifecycle of a page would look like this:

-

HTML loaded from storage directly into page.

-

HTML converted once to LML for editing.

-

As LML edited, the HTML view is updated immediately to display the changes.

-

Saving changes is simply writing the HTML preview back to storage!

In the drawing above, the split-pane editor has the HTML page "preview" on the left side and the LML code editor on the right side.

The so-called "preview" is initially the HTML page exactly as loaded from disk. It gets updated when you make changes to the LML. When you save your changes, the "preview" is saved back to disk.

Okay, simple enough. But isn’t this just shifting complexity around, not eliminating it? Maybe. That’s a fair question.

In practice, this does seem to have some real benefits. Read on!

Trying it out

Incredibly, I was able to get the basics working in just one evening. The key to success: Extreme simplicity!

The two-pane editor remains identical in appearance, but I scrapped the two-way WYSIWYG and HTML code sync and replaced it with a more traditional one-way sync from the LML code view to the "rendered" HTML view.

As I often do with DSLs, I have restricted the HTML WARDen LML to a line-based format, like the roff (wikipedia.org) formats of yore. This means that there is no tricky inline formatting (like '*' for bold). EXTREME SIMPLICITY!

Putting the Lightweight in Lightweight Markup Language

The HTML WARDen LML supports a tiny number of elements. Just what I need for this project and not a single thing extra:

-

A page title (the first line of the document).

-

Paragraphs of text separated by blank lines.

-

Internal and external links.

-

Two heading levels.

Here’s a syntax cheatsheet:

= Heading == Sub-Heading internal_page_link[] page_link[Page Link With Display Text] http://example.com[External Link]

The page editing button interface also needed an update, but mostly I removed formatting features and replaced them with a Help button that displays the above cheatsheet.

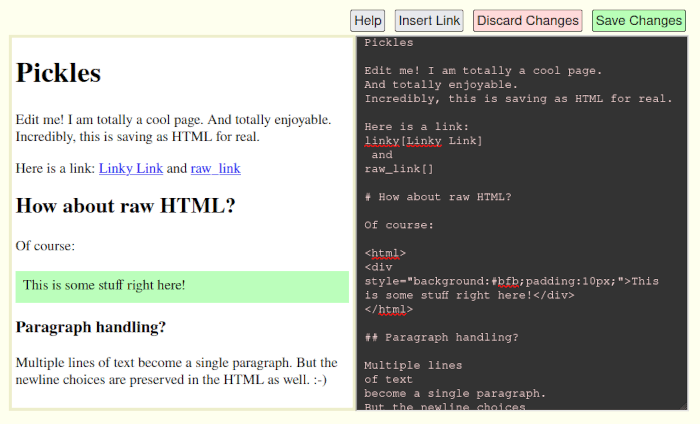

Arbitrary HTML still okay

Wait, but isn’t that LML too limited? What if I need to create or include something a little more complex in a page - can I still edit it?

Absolutely. The final syntax feature of the LML is the ability to have arbitrary

HTML that doesn’t have a direct equivalent still exist, but be left alone. Any

HTML not understood by HTML WARDen’s editor is automatically enclosed by a

protective bubble of start and end <html></html> tags and left verbatim. You

can edit the raw HTML if you want, but the editor itself won’t mess with it.

You can see an example of that in this screenshot of the new editor interface:

As you can see on the left side, there’s a green box. And on the right side, you can see that it’s just a chunk of raw HTML with inline style like so:

<html> <div style="background:#bfb;padding:10px;">...<div> </html>

This "escape hatch" may feel like cheating, but it’s not.

Line-based parsers are so easy

The LML parser is 71 lines of, honestly, pretty trashy code.

Here’s the bulk of it:

var rx_h2=/^# (.*)$/;

var rx_h3=/^## (.*)$/;

var rx_a=/^([^[]+)\[(.*)\]/;

var rx_html=/^\<html\>$/;

var rx_end_html=/^\<\/html\>$/;

var rx_blank=/^\s*$/;

...

var lines = code_area.value.split(/\r\n|\r|\n/);

var para_open = false;

// Title always first

var title = lines[0];

if(title.length < 1){ title = "Untitled"; }

var html = "<h1>" + title + "</h1>\n";

for(var i=1; i<lines.length; i++){

line = lines[i];

if(m = rx_h2.exec(line)){ close_p(); html += '<h2>' + m[1] + '</h2>\n'; continue; }

if(m = rx_h3.exec(line)){ close_p(); html += '<h3>' + m[1] + '</h3>\n'; continue; }

...

// Blank line ends current p, if we're in one

if(rx_blank.test(line)){

close_p();

continue;

}

// Else, we've got paragraph content

open_p();

html += line + "\n";

}

html_view.innerHTML = html;

The hardest part, as is the case with these things, is just keeping track of whether or not we’re currently in a paragraph.

So that’s the LML to HTML conversion, but…

Wait, but one does not simply parse HTML!

There’s still the initial one-time conversion of HTML to LML to populate the code editor pane. Trying to parse even a tiny subset of HTML is going to be fraught with danger, right?

So…the other fun thing about working with HTML in a browser is…you have the most powerful piece of HTML parsing software ever created right at your fingertips.

How do I parse the HTML? I don’t! I’m accessing the DOM of the page from JavaScript. It’s just 43 lines of, again, trashy code. Here’s most of it:

// Start by writing title as the first line

var title_tag = html_view.querySelector('h1');

var txt = title_tag ? title_tag.textContent : 'Untitled';

if(txt.length < 1){ txt = 'Untitled'; }

txt += "\n\n";

// old skool 'for' loop required for element collection

for(var i=0; i<html_view.children.length; i++){

e = html_view.children[i];

switch(e.nodeName){

case 'H1': continue; // We've already taken care of the title

case 'H2': p = '# ' + e.textContent + "\n\n"; break;

case 'H3': p = '## ' + e.textContent + "\n\n"; break;

...

case 'P':

p='';

for(j=0; j<e.childNodes.length; j++){

if(e2.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE){ ...

if(e2.nodeType === Node.ELEMENT_NODE){

if(e2.nodeName === 'A'){

...

}

}

}

p += "\n";

break;

default: p = '<html>\n' + e.outerHTML + '\n</html>\n\n';

}

txt += p;

}

code_area.value = txt;

}

The DOM API ain’t pretty, but compared to parsing HTML myself, it’s very, very nice.

It works!

It’s not as "easy" as just using the browser-supplied WYSIWYG editor and doing everything as HTML with no conversion at all. But it’s way nicer to use and very effective. I actually enjoy editing pages like this. I don’t feel like I’m fighting it.

Even though I’ve introduced a new LML and a conversion process to the situation, it was surprisingly painless to change direction.

Now I feel like I’m getting the benefits of traditional wiki quick authoring and the benefits of HTML storage.

Benefit: No conversion needed to view

The HTML seen in the "preview" pane of the editor is the page. It’s the exact source that is saved when you’re done editing.

Zero processing is needed to view the wiki, I’m still just including the content

of the file with PHP’s include statement.

Benefit: HTML is the One True Final storage format for HTML

Incredibly, making this huge change to page editing had zero

impact on the rest of the wiki. The only file affected by that

commit was edit.php, and only the editor portion of that.

Using HTML as the storage format means not having to convert between storage formats ever again

(This is one reason I’ve been excited about maybe someday moving to this method for ratfactor.com. If I switched from AsciiDoc to, say, Markdown or some other LML, I’d have to convert all of my stored pages. Yuck! But if I convert to HTML…I’m already done! I already have the exported static site.)

Benefit: Static pages for a potential static site

As I mentioned in Wiki Weekend Part 3, the pages are stored as incomplete HTML documents missing a head and foot.

Browsers, tolerant beasts that they are, will happily render the partial pages despite the missing tags. Which means that, in some sense, the stored page fragments are a static website.

I’ve been mulling over several different ways I might handle a bigger and more complex static HTML site with real, complete pages. I’m not ready for that just yet and there are a lot of ways I would want to improve the LML experience for that. But it’s clearly possible!

So, HTML WARDen is also proof of concept for a future wiki-style editor for a complete, proper static website where documents sit on disk as HTML ready to be served as-is and ready to be edited as LML.

What’s next?

Next is image handling. There will be one more bit of syntax in the LML to represent images. I’ll have file uploads with visual progress. I’ll also need to generate thumbnails and make a mini gallery with a search feature to find previously uploaded images.

Stay tuned.