RetroV: Why use a VDOM?

Page created: 2023-03-24 , updated: 2023-04-05Back to the RetroV main page.

To understand why a "virtual DOM" is so compelling, I think it’s important to contrast it with the alternative.

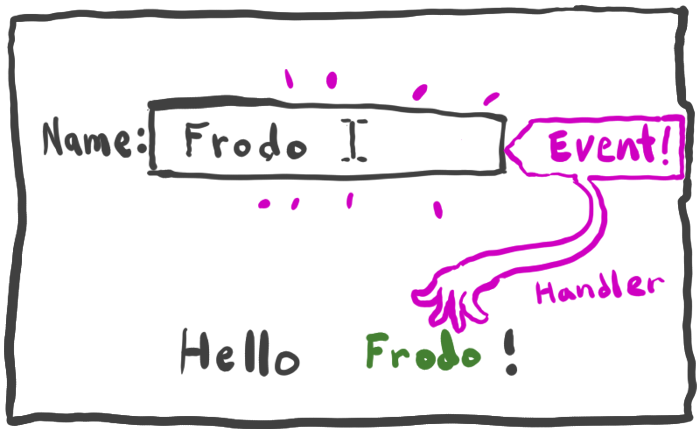

The alternative is the "obvious" way to do it: when some bit of state changes, you go in and change the document (via the DOM) to match the state.

Actually…

Historically speaking, we started out rendering everything on the server and delivered static HTML documents. The session’s "state" was handled via entire documents as the interface. User interaction was through form submission.

As you’ll see in a bit, VDOMs let us come full circle to the simplicity of this model.

In the beginning

The DHTML ("Dynamic HTML") era is where we first realized

we could make dynamic changes to HTML with JavaScript. We stored primitive

state in hidden form <input> fields. We made weird drop-down menus and

displayed lots of alert boxes. But it wasn’t all silly.

Client-side form validation made things

much nicer since you no longer had to wait for a full round-trip to the

server (over a modem) to see if you typed your credit card number incorrectly.

There were huge compatibility problems between the browsers (e.g. Netscape and Microsoft) and almost no debugging tools. It was only fun and exciting because it was new.

Tools like jQuery helped us smooth over the browser differences, but the principle was the same: as state changes, you change the DOM to reflect the changes.

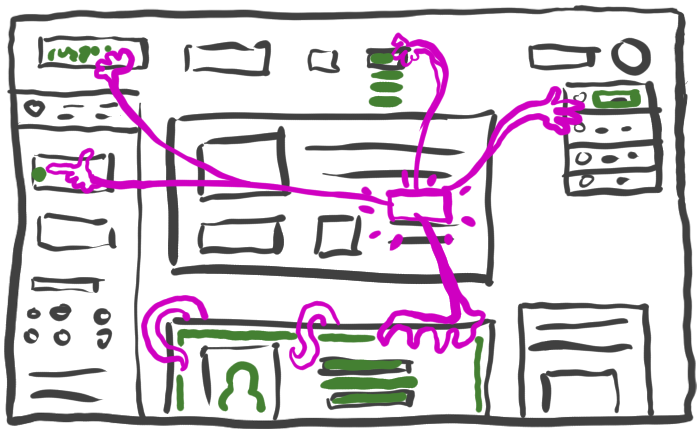

But then we started to build SPAs (Single Page Applications) and expectations grew and complexity increased. The interfaces became sophisticated and intertwined. Direct DOM manipulations started to get hard to manage. Really hard.

The common comparison application, TodoMVC, is a great example of the sorts of tricky interface challenges that are hard to cover completely when you have to directly manipulate the UI. You can see my implementation in RetroV here.

(To make matters even worse, a lot of us were still used to storing bits of state in the DOM. So you’d actually read data from part of the interface to write to another part. And yes, that’s just as awful and hard to maintain as it sounds.)

Of course, it is possible to build things this way. But you end up with what they call in the watch-making world, a grand complication.

Rise of the VDOM

Enter React. Well, actually, for me, enter Mithril (mithril.js.org). Mithril is a small, cohesive library that, like React, uses a VDOM implementation to render "views" into the real HTML DOM. Mithril’s author, Leo Horie, wrote a series of blog posts (lhorie.github.io) with lucid explanations that helped me begin to understand the whole lifecycle of a VDOM application.

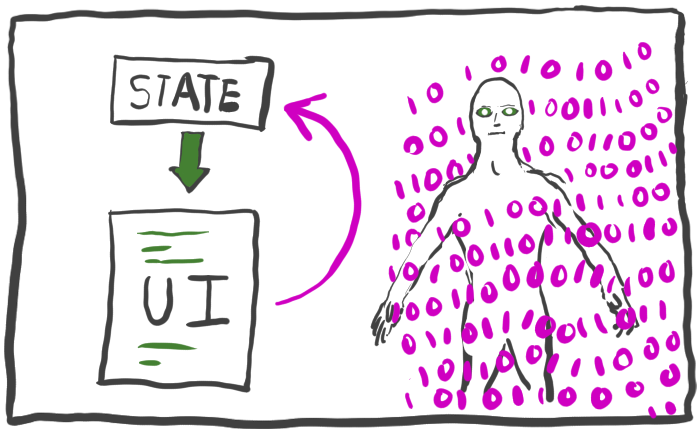

The brilliance of the VDOM paradigm is this: It lets you look at a really complicated interface and say, "Screw it, let’s just re-render the whole thing!"

This is awesome because if you can just re-render the whole thing, then it suddenly becomes much easier to reason about the state of the DOM because all of the micromanagement is gone.

It’s like the old days when performing an action meant a whole new document would come back from the server.

The state has changed. There’s your new document. Done!

There are two reasons we needed something like a VDOM to take this "re-render the whole thing" approach:

-

Browsers at the time couldn’t perform JavaScript DOM manipulations fast enough to re-render an entire interface without it becoming a performance problem. (Even if they could, it’s still wasteful of energy and makes polar bears cry.)

-

Some HTML elements such as form element change their own state when users interact with them. This state is lost if the element is destroyed and re-created. So we can’t really just replace everything unless we have a way of restoring that state into the new elements.

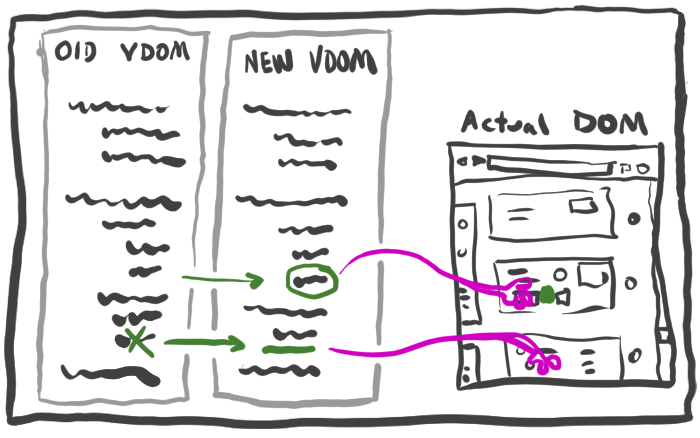

A VDOM "diffing" library solves these problems by comparing two trees: The old virtual DOM is a JavaScript data structure representing the HTML elements which have previously been rendered. The new virtual DOM is another data structure (probably nearly identical) with the new state we wish to have.

Only the differences between the two trees actually result in changes to the real DOM.

In practice, comparing two reasonably-sized data structures in memory is lightning fast (and outside of pathological cases, most UIs are really, really tiny in terms of data structures). So VDOMs have been associated with speed.

(Aside: There’s an article called Virtual DOM is pure overhead (svelte.dev) which comes up a lot. Everything in the article is correct and it’s quite insightful in general: "It’s important to understand that virtual DOM isn’t a feature. It’s a means to an end, the end being declarative, state-driven UI development." That’s absolutely right. But keep in mind that the alternative presented by Svelte is a build tool. An application written in Svelte cannot be run in the browser until it passes through the Svelte tooling. That’s great, but I think we can agree that the comparison between a compiler and an in-browser library is a bit apples and oranges.)

It’s practically a philosophy

Beyond just the technical aspects, using a VDOM library opens the door to completely re-thinking how state flows through the application.

It’s a quick path from jQuery to VDOMs to point-free functional programming, immutable data structures, replacing logical operators with combinators and finally, complete raving madness and foaming at the mouth about "functors" (whatever the heck those are).

But seriously, it radically changes how you build interfaces.

I think it’s a lot like software testing; it makes your program better not just because of the explicit benefits, but because it makes you re-think the logic and structure of your application. Testable programs probably have better modularity. VDOM UIs probably have better separation of concerns.

UI as data

The only possible downside of VDOMs (assuming performance is not an issue) are that they can seem somewhat magical until you understand how they work.

Magic isn’t always good if it obscures understanding.

But there’s nothing magic going on. It really is as simple as I outlined above: an old and new VDOM tree are compared. As each change between the two are detected, the DOM is updated to perform the change in the real interface. That’s it.

RetroV doubles down on the idea that VDOMs are just data. It has no methods for creating them. Instead, you supply your new state as a simple array-based tree of elements.

['ul',

['li', 'Rain'],

['li', 'Snow'],

['li', 'Fog'],

]

The huge advantage of this is that you have the full expressive power of the JavaScript programming language with which to create your interface. You already know JavaScript, so the only new thing to learn is the data structure. (And you just learned most of that in the example above.)

It also means you can always create your own abstractions for interface creation as you discover the need and to suit your tastes.

Unlike consumers of larger libraries, I expect RetroV users (such as myself) to build small libraries of tailored helper functions specific to their application. RetroV is just the renderer underneath.

Performance

Are VDOMs really fast enough?

Yes.

I mean, of course you can come up with torture tests that break a

VDOM engine. But take a look at the RetroV test.html

page. At the time of this writing, it renders 118 different tiny

tests in a visible <div> at the bottom of the page and they all happen

so fast you’ll probably never

see them (they happen before the browser even performs the first paint).

(Update: And now all that happens twice on startup - once for the normal library and one for the minified copy.)

Most "normal" interfaces are no problem. If you need to display 10,000 elements on the screen or something, find a high-performance library…or write something custom. You have my blessing.

But VDOMs are not about speed. They’re about simplifying the way you write interfaces. "Fast enough" is perfect.

See also: How RetroV Works.